Chapter 14 Git Branches

While git is great for uploading and downloading code, its true benefits are its ability to support reversability (e.g., undo) and collaboration (working with other people). In order to effectively utilize these capabilities, you need to understand git’s branching model, which is central to how the program manages different versions of code.

This chapter will cover how to work with branches with git and GitHub, including using them to work on different features simultaneously and to undo previous changes.

14.1 Git Branches

So far, you’ve been using git to create a linear sequence of commits: they are all in a line, one after another).

A linear sequence of commits, each with an SHA1 identifier.

Each commit has a message associated with it (that you can see with git log --oneline), as well as a unique SHA-1 hash (the random numbers and letters), which can be used to identify that commit as an “id number”.

But you can also save commits in a non-linear sequence. Perhaps you want to try something new and crazy without breaking code that you’ve already written. Or you want to work on two different features simultaneously (having separate commits for each). Or you want multiple people to work on the same code without stepping on each other’s toes.

To do this, you use a feature of git called branching (because you can have commits that “branch off” from a line of development):

An example of branching commits.

In this example, you have a primary branch (called the master branch), and decide you want to try an experiment. You split off a new branch (called for example experiment), which saves some funky changes to your code. But then you decide to make further changes to your main development line, adding more commits to master that ignore the changes stored in the experiment branch. You can develop master and experiment simultaneously, making changes to each version of the code. You can even branch off further versions (e.g., a bugfix to fix a problem) if you wish. And once you decide you’re happy with the code added to both versions, you can merge them back together, so that the master branch now contains all the changes that were made on the experiment branch. If you decided that the experiment didn’t work out, you can simply delete those set of changes without ever having messed with your “core” master branch.

You can view a list of current branches in the repo with the command

(The item with the asterisk (*) is the “current branch” you’re on. The latest commit of the branch you’re on is referred to as the HEAD.

You can use the same command to create a new branch:

This will create a new branch called branch_name (replacing [branch_name], including the brackets, with whatever name you want). Note that if you run git branch again you’ll see that this hasn’t actually changed what branch you’re on. In fact, all you’ve done is created a new reference (like a new variable!) that refers to the current commit as the given branch name.

You can think of this like creating a new variable called

branch_nameand assigning the latest commit to that! Almost like you wrotenew_branch <- my_last_commit.If you’re familiar with LinkedLists, it’s a similar idea to changing a pointer in those.

In order to switch to a different branch, use the command (without the brackets)

Checking out a branch doesn’t actually create a new commit! All it does is change the HEAD (the “commit I’m currently looking at”) so that it now refers to the latest commit of the target branch. You can confirm that the branch has changed with git branch.

You can think of this like assigning a new value (the latest commit of the target branch) to the

HEADvariable. Almost like you wroteHEAD <- branch_name_last_commit.Note that you can create and checkout a branch in a single step using the

-boption ofgit checkout:

Once you’ve checked out a particular branch, any new commits from that point on will be “attached” to the “HEAD” of that branch, while the “HEAD” of other branches (e.g., master) will stay the same. If you use git checkout again, you can switch back to the other branch.

- Important checking out a branch will “reset” your code to whatever it looked like when you made that commit. Switch back and forth between branches and watch your code change!

Switching between the HEAD of different branches.

Note that you can only check out code if the current working directory has no uncommitted changes. This means you’ll need to commit any changes to the current branch before you checkout another. If you want to “save” your changes but don’t want to commit to them, you can also use git’s ability to temporarily stash changes.

Finally, you can delete a branch using git branch -d [branch_name]. Note that this will give you a warning if you might lose work; be sure and read the output message!

14.2 Merging

If you have changes (commits) spread across multiple branches, eventually you’ll want to combine those changes back into a single branch. This is a process called merging: you “merge” the changes from one branch into another. You do this with the (surprise!) merge command:

This command will merge other_branch into the current branch. So if you want to end up with the “combined” version of your commits on a particular branch, you’ll need to switch to (checkout) that branch before you run the merge.

IMPORTANT If something goes wrong, don’t panic and try to close your command-line! Come back to this book and look up how to fix the problem you’ve encountered (e.g., how to exit vim). And if you’re unsure why something isn’t working with git, use

git statusto check the current status and for what steps to do next.Note that the

rebasecommand will perform a similar operation, but without creating a new “merge” commit—it simply takes the commits from one branch and attaches them to the end of the other. This effectively changes history, since it is no longer clear where the branching occurred. From an archival and academic view, you never want to “destroy history” and lose a record of changes that were made. History is important: don’t screw with it! Thus we recommend you avoid rebasing and stick with merging.

14.2.1 Merge Conflicts

Merging is a regular occurrence when working with branches. But consider the following situation:

- You’re on the

masterbranch. - You create and

checkouta new branch calleddanger - On the

dangerbranch, you change line 12 of the code to be “I like kitties”. You then commit this change (with message “Change line 12 of danger”). - You

checkout(switch to) themasterbranch again. - On the

masterbranch, you change to line 12 of the code to be “I like puppies”. You then commit this change (with message “Change line 12 of master”). - You use

git merge dangerto merge thedangerbranch into themasterbranch.

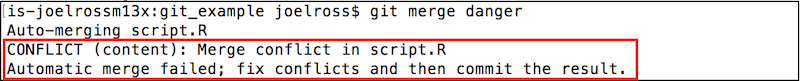

In this situation, you are trying to merge two different changes to the same line of code, and thus should be shown an error on the command-line:

A merge conflict reported on the command-line

This is called a merge conflict. A merge conflict occurs when two commits from different branches include different changes to the same code (they conflict). Git is just a simple computer program, and has no way of knowing which version to keep (“Are kitties better than puppies? How should I know?!”).

Since git can’t determine which version of the code to keep, it stops the merge in the middle and forces you to choose what code is correct manually.

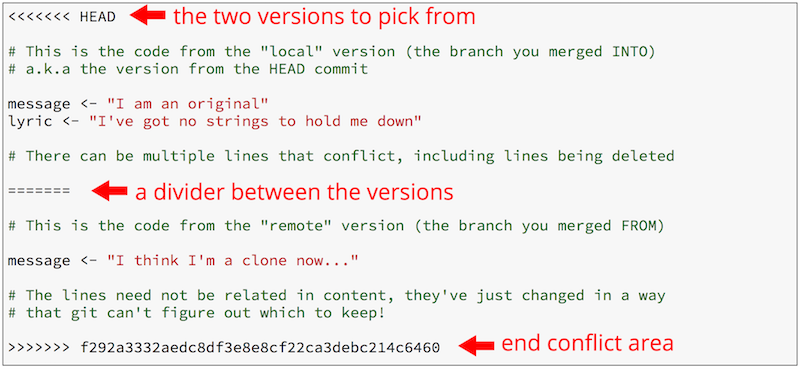

In order to resolve the merge conflict, you will need to edit the file (code) so that you pick which version to keep. Git adds “code” to the file to indicate where you need to make a decision about which code is better:

Code including a merge conflict.

In order to resolve the conflict:

Use

git statusto see which files have merge conflicts. Note that files may have more than one conflict!Choose which version of the code to keep (or keep a combination, or replace it with something new entirely!) You do this by editing the file (i.e., open it in Atom or RStudio and change it). Pretend that your cat walked across your keyboard and added a bunch of extra junk; it is now your task to fix your work and restore it to a clean, working state. Be sure and test your changes to make sure things work!

Be sure and remove the

<<<<<<<and=======and>>>>>>>. These are not legal code in any language.Once you’re satisfied that the conflicts are all resolved and everything works as it should, follow the instructions in the error message and

addandcommityour changes (the code you “modified” to resolve the conflict):This will complete the merge! Use

git statusto check that everything is clean again.

Merge conflicts are expected. You didn’t do something wrong if one occurs! Don’t worry about getting merge conflicts or try to avoid them: just resolve the conflict, fix the “bug” that has appeared, and move on with your life.

14.3 Undoing Changes

One of the key benefits of version control systems is reversibility: the ability to “undo” a mistake (and we all make lots of mistakes when programming!) Git provides two basic ways that you can go back and fix a mistake you’ve made previously:

You can replace a file (or the entire project directory!) with a version saved as a previous commit.

You can have git “reverse” the changes that you made with a previous commit, effectively applying the opposite changes and thereby undoing it.

Note that both of these require you to have committed a working version of the code you want to go back to. Git only knows about changes that have been committed—if you don’t commit, git can’t help you! Commit early, commit often.

For both forms of undoing, first recall how each commit has a unique SHA-1 hash (those random numbers) that acted as its “name”. You can see these with the git log --oneline command.

You can use the checkout command to switch not only to the commit named by a branch (e.g., master or experiment), but to any commit in order to “undo” work. You refer to the commit by its hash number in order to check it out:

This will replace the current version of a single file with the version saved in commit_number. You can also use -- as the commit-number to refer to the HEAD (the most recent commit in the branch):

If you’re trying to undo changes to lots of files, you can alternatively replace the entire project directory with a version from a previous commit by checking out that commit as a new branch:

This command treats the commit as if it was the HEAD of a named branch… where the name of that branch is the commit number. You can then make further changes and merge it back into your development or master branch.

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you don’t create a new branch (with -b) when checking out an old commit, you’ll enter detached HEAD state. You can’t commit from here, because there is no branch for that commit to be attached to! See this tutorial (scroll down) for details and diagrams. If you find yourself in a detached HEAD state, you can use git checkout master to get back to the last saved commit (though you will lose any changes you made in that detached state—so just avoid it in the first place!)

But what if you just had one bad commit, and don’t want to throw out other good changes you made later? For this, you can use the git revert command:

This will determine what changes that commit made to the files, and then apply the opposite changes to effectively “back out” the commit. Note that this does not go back to the given commit number (that’s what checkout is for!), but rather will reverse the commit you specify.

This command does create a new commit (the

--no-editoption tells git that you don’t want to include a custom commit message). This is great from an archival point of view: you never “destroy history” and lose the record of what changes were made and then reverted. History is important: don’t screw with it!Conversely, the

resetcommand will destroy history. Do not use it, no matter what StackOverflow tells you to do.

14.4 GitHub and Branches

GitHub is an online service that stores copies of repositories in the cloud. When you push and pull to GitHub, what you’re actually doing is merging your commits with the ones on GitHub!

However, remember that you don’t edit any files on GitHub’s servers, only on your own local machine. And since resolving a merge conflict involves editing the files, you have to be careful that conflicts only occur on the local machine, not on GitHub. This plays out in two ways:

You will not be able to

pushto GitHub if merging your commits into GitHub’s repo would cause a merge conflict. Git will instead report an error, telling you that you need topullchanges first and make sure that your version is “up to date”. Up to date in this case means that you have downloaded and merged all the commits on your local machine, so there is no chance of divergent changes causing a merge conflict when you merge by pushing.Whenever you

pullchanges from GitHub, there may be a merge conflict! These are resolved in the exact same way as when merging local branches: that is, you need to edit the files to resolve the conflict, thenaddandcommitthe updated versions.

Thus in practice, when working with GitHub (and especially with multiple people), in order to upload your changes you’ll need to do the following:

pull(download) any changes you don’t have- Resolve any merge conflicts that occurred

push(upload) your merged set of changes

Additionally, because GitHub repositories are repos just like the ones on your local machine, they can have branches as well! You have access to any remote branches when you clone a repo; you can see a list of them with git branch -a (using the “all” option).

If you create a new branch on your local machine, it is possible to push that branch to GitHub, creating a mirroring branch on the remote repo. You do this by specifying the branch in the git push command:

where branch_name is the name of the branch you are currently on (and thus want to push to GitHub).

Note that you often want to associate your local branch with the remote one (make the local branch track the remote), so that when you use git status you will be able to see whether they are different or not. You can establish this relationship by including the -u option in your push:

Tracking will be remembered once set up, so you only need to use the -u option once.

14.4.1 GitHub Pages

GitHub’s use of branches provides a number of additional features, one of which is the ability to host web pages (.html files, which can be generated from R Markdown) on a publicly accessible web server that can “serve” the page to anyone who requests it. This feature is known as GitHub Pages.

With GitHub pages, GitHub will automatically serve your files to visitors as long as the files are in a branch with a magic name: gh-pages. Thus in order to publish your webpage and make it available online, all you need to do is create that branch, merge your content into it, and then push that branch to GitHub.

You almost always want to create the new gh-pages branch off of your master branch. This is because you usually want to publish the “finished” version, which is traditionally represented by the master branch. This means you’ll need to switch over to master, and then create a new branch from there:

Checking out the new branch will create it with all of the commits of its source meaning gh-pages will start with the exact same content as master—if your page is done, then it is ready to go!

You can then upload this new local branch to the gh-pages branch on the origin remote:

After the push completes, you will be able to see your web page using the following URL:

https://GITHUB-USERNAME.github.io/REPO-NAME(Replace GITHUB-USERNAME with the user name of the account hosting the repo, and REPO-NAME with your repository name).

- This means that if you’re making your homework reports available, the

GITHUB-USERNAMEwill be the name of the course organization.

Some important notes:

The

gh-pagesbranch must be named exactly that. If you misspell the name, or use an underscore instead of a dash, it won’t work.Only the files and commits in the

gh-pagesbranch are visible on the web. All commits in other branches (experiment,master, etc.) are not visible on the web (other than as source code in the repo). This allows you to work on your site with others before publishing those changes to the web.Any content in the

gh-pagesbranch will be publicly accessible, even if your repo is private. You can remove specific files from thegh-pagesbranch that you don’t want to be visible on the web, while still keeping them in themasterbranch: use thegit rmto remove the file and then add, commit, and push the deletion.- Be careful not push any passwords or anything to GitHub!

The web page will only be initially built when a repo administrator pushes a change to the

gh-pagesbranch; if someone just has “write access” to the repo (e.g., they are a contributor, but not an “owner”), then the page won’t be created. But once an administrator (such as the person who created the repo) pushes that branch and causes the initial page to be created, then any further updates will appear as well.

After you’ve created your initial gh-pages branch, any changes you want to appear online will need to be saved as new commits to that branch and then pushed back up to GitHub. HOWEVER, it is best practice to not make any changes directly to the gh-pages branch! Instead, you should switch back to the master branch, make your changes there, commit them, then merge them back into gh-pages before pushing to GitHub:

# switch back to master

git checkout master

### UPDATE YOUR CODE (outside of the terminal)

# commit the changes

git add .

git commit -m "YOUR CHANGE MESSAGE"

# switch back to gh-pages and merge changes from master

git checkout gh-pages

git merge master

# upload to github

git push --all(the --all option on git push will push all branches that are tracking remote branches).

This procedure will keep your code synchronized between the branches, while avoiding a large number of merge conflicts.

Resources

- Git and GitHub in Plain English

- Atlassian Git Branches Tutorial

- Git Branching (Official Documentation)

- Learn Git Branching (interactive tutorial)

- Visualizing Git Concepts (interactive visualization)

- Resolving a merge conflict (GitHub)